Coming in Hot: NASA's Chandra Checks Habitability of Exoplanets

Your browser does not support the video tag.

A Three-dimensional Map of Stars Near the Sun

Credit: Movie: Cal Poly Pomona/B. Binder; Illustration: NASA/CXC/M.Weiss

This graphic shows a three-dimensional map of stars near the Sun. These stars are close enough that they could be prime targets for direct imaging searches for planets using future telescopes. The blue haloes represent stars that have been observed with NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and ESA’s XMM-Newton. The yellow star at the center of this diagram represents the position of the Sun. The concentric rings show distances of 5, 10, and 15 parsecs (one parsec is equivalent to roughly 3.2 light-years).

Astronomers are using these X-ray data to determine how habitable exoplanets may be based on whether they receive lethal radiation from the stars they orbit, as described in our latest press release. This type of research will help guide observations with the next generation of telescopes aiming to make the first images of planets like Earth.

Red Sox NASA STEM Day & Chandra’s 25th anniversary

Before the first pitch of the Red Sox game on June 5th, over 3,000 local New England students were treated to a morning of STEM (“science, technology, engineering and math”) programs for the Red Sox NASA STEM Day. As local representatives of NASA in New England, the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO), including Chandra, had a huge presence and helped to celebrate the Chandra telescope’s 25th anniversary!

How do Supermassive Black Holes Get Super Massive?

3C 58

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/ICE-CSIC/A. Marino et al.; Optical: SDSS; Image Processing: NASA/CXC/SAO/J. Major

The supernova remnant 3C 58 contains a spinning neutron star, known as PSR J0205+6449, at its center. Astronomers studied this neutron star and others like it to probe the nature of matter inside these very dense objects. A new study, made using NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and ESA’s XMM-Newton, reveals that the interiors of neutron stars may contain a type of ultra-dense matter not found anywhere else in the Universe.

In this image of 3C 58, low-energy X-rays are colored red, medium-energy X-rays are green, and the high-energy band of X-rays is shown in blue. The X-ray data have been combined with an optical image in yellow from the Digitized Sky Survey. The Chandra data show that the rapidly rotating neutron star (also known as a “pulsar”) at the center is surrounded by a torus of X-ray emission and a jet that extends for several light-years. The optical data shows stars in the field.

'Super' Star Cluster Shines in New Look From NASA's Chandra

Westerlund 1

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/INAF/M. Guarcello et al.; Optical: NASA/ESA/STScI;

Image Processing: NASA/CXC/SAO/L. Frattare

Westerlund 1 is the biggest and closest “super” star cluster to Earth. New data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, in combination with other NASA telescopes, is helping astronomers delve deeper into this galactic factory where stars are vigorously being produced.

This is the first data to be publicly released from a project called the Extended Westerlund 1 and 2 Open Clusters Survey, or EWOCS, led by astronomers from the Italian National Institute of Astrophysics in Palermo. As part of EWOCS, Chandra observed Westerlund 1 for about 12 days in total.

Dr. Tananbaum Awarded NASA Distinguished Public Service Medal

Dr. Harvey Tananbaum receiving the NASA Distinguished Public Service Medal

Credit: NASA/Glenn Research Center

On March 28, 2024, Harvey Tananbaum was awarded the NASA Distinguished Public Service Medal during a ceremony at the Glenn Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio.

Dr. Tananbaum was recognized for his distinguished career that has made X-ray astronomy a bedrock observational discipline for the advancement of astrophysics, and his leadership in NASA X-ray space telescopes like the Chandra X-ray Observatory made NASA the world leader in X-ray astronomy missions.

The citation for this award highlights his “outstanding contributions to NASA’s science mission through key roles in pioneering X-ray astronomy missions that have revolutionized our understanding of the universe.”

Shown left to right in this photo: James Free (NASA Associate Administrator), Harvey Tananbaum (SAO/CXC), Casey Swails (NASA Deputy Associate Administrator)

- Megan Watzke

Chandra Enters Through the Sidedoor (Podcast)

Did you know that the Smithsonian has a podcast? It’s called Sidedoor and it gives listeners a behind-the-scenes look into the Smithsonian’s museums and research units. One of those research units is the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, which has run NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory since before launch and continues to control its flight and science operations to this day.

On the latest episode of Sidedoor, Dr. Kimberly Arcand (Chandra’s visualization scientist and emerging tech lead), along with Dr. Priyamvada Natarajan (astrophysicist, and professor at Yale University) and Dr. Arthur I. Miller, (scientist and author), discuss black holes and the connection to Dr. Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, the namesake of the Chandra X-ray Observatory. Listen to the first installment of this two-part journey through the cosmos at https://www.si.edu/sidedoor/cosmic-journey-i-stellar-buffoonery

Spotted: 'Death Star' Black Holes in Action

Black Hole "Death Stars," Abell 478 & NGC 5044

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/Univ. of Chicago/S.C. Mackey et al.; Radio: NRF/SARAO/MeerKAT; Image Processing: NASA/CXC/SAO/N. Wolk

A team of astronomers have studied 16 supermassive black holes that are firing powerful beams into space, to track where these beams, or jets, are pointing now and where they were aimed in the past, as reported in our latest press release. Using NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) National Radio Astronomical Observatory’s (NRAO) Very Large Baseline Array (VLBA), they found that some of the beams have changed directions by large amounts.

These two Chandra images show hot gas in the middle of the galaxy cluster Abell 478 (left) and the galaxy group NGC 5044 (right). The center of each image contains one of the sixteen black holes firing beams outwards. Each black hole is in the center of a galaxy embedded in the hot gas.

By mousing over the images, labels and the radio images appear. Ellipses show a pair of cavities in the hot gas for Abell 478 (left) and ellipses show two pairs of cavities for NGC 5044 (right). These cavities were carved out by the beams millions of years ago, giving the directions of the beams in the past. An X shows the location of each supermassive black hole.

NASA's Chandra Notices the Galactic Center is Venting

Galactic Center Vent

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/Univ. of Chicago/S.C. Mackey et al.; Radio: NRF/SARAO/MeerKAT; Image Processing: NASA/CXC/SAO/N. Wolk

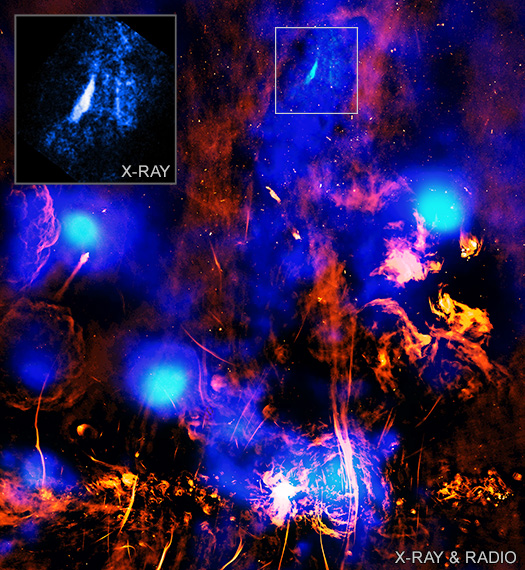

These images show evidence for an exhaust vent attached to a chimney releasing hot gas from a region around the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way, as reported in our latest press release. In the main image of this graphic, X-rays from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory (blue) have been combined with radio data from the MeerKAT telescope (red).

Previously, astronomers had identified a “chimney” of hot gas near the Galactic Center using X-ray data from Chandra and ESA’s XMM-Newton. Radio emission detected by MeerKAT shows the effect of magnetic fields enclosing the gas in the chimney.

The evidence for the exhaust vent is highlighted in the inset, which includes only Chandra data. Several X-ray ridges showing brighter X-rays appear in white, roughly perpendicular to the plane of the Galaxy. Researchers think these are the walls of a tunnel, shaped like a cylinder, which helps funnel hot gas as it moves upwards along the chimney and away from the Galactic Center.

The Genesis of Giants: Tracing the Early Development of Supermassive Black Holes

We welcome Orsolya Eszter Kovács, a postdoctoral fellow at Masaryk University, Czechia, as our guest blogger. She spent over two years at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory as a pre-doctoral fellow while working on the PhD she obtained from Eötvös Loránd University, Hungary. She is the first author of a recent paper presenting one of the most distant supermassive black holes ever seen.

In the past six months1 Chandra has unveiled two supermassive black holes remarkably close to their formation epoch, only about 500 million years after the big bang. These findings mark some of the most distant supermassive black holes observed to date.

Supermassive black holes, the largest type of black holes, lurk in the heart of most big galaxies. These cosmic behemoths play a central role in the formation and evolution of their hosting galaxies, exerting influence so significant that they can even suppress star formation.

The origin of these giant black holes is a subject of debate. Do they originate from the collapse of the earliest stellar population, known as Population III stars? Although it seems like an obvious explanation, to reach those immense masses observed in their later stages, these “light black hole seeds” need to be fed with an extreme amount of matter in a relatively brief period (through a process that astronomers call “accretion”). Yet, such a high accretion rate seems improbable as a universal solution, because there are physical limits on how quickly material can fall inwards. The outwards pressure from the intense radiation associated with high accretion can overcome the gravitational forces pulling material inwards, causing the material to be pushed away instead.

NASA's Chandra Releases Doubleheader of Blockbuster Hits

Your browser does not support the video tag.

Crab Nebula and Cassiopeia A

Credit: Cassiopeia A: X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO; Optical: NASA/STScI; Image Processing: NASA/CXC/SAO/J. Major, A. Jubett, K. Arcand; Crab Nebula: X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO; Image processing: NASA/CXC/SAO/J. Schmidt, J. Major, A. Jubett, K. Arcand

New movies of two of the most famous objects in the sky — the Crab Nebula and Cassiopeia A — are being released from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory. Each includes X-ray data collected by Chandra over about two decades. They show dramatic changes in the debris and radiation remaining after the explosion of two massive stars in our galaxy.

The Crab Nebula, the result of a bright supernova explosion seen by Chinese and other astronomers in the year 1054, is 6,500 light-years from Earth. At its center is a neutron star, a super-dense compact object produced by the supernova. As it rotates at about 30 times per second, its beam of radiation passes over the Earth every rotation, like a cosmic lighthouse.

As the young pulsar slows down, large amounts of energy are injected into its surroundings. In particular, a high-speed wind of matter and anti-matter particles plows into the surrounding nebula, creating a shock wave that forms the ring seen in the movie. Jets from the poles of the pulsar spew X-ray emitting matter and antimatter particles in a direction perpendicular to the ring.