IXPE and Chandra Untangle Theories Surrounding Historic Supernova Remnant

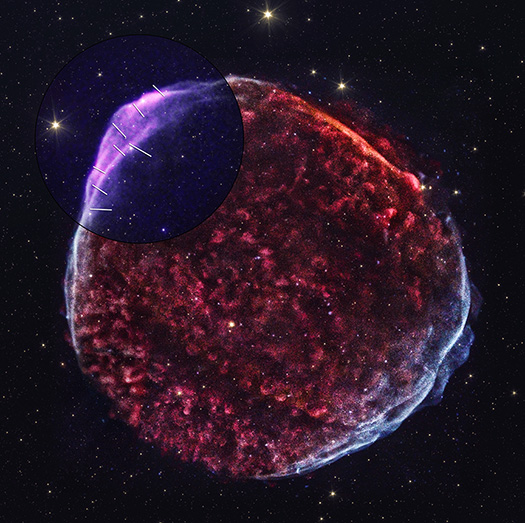

SN 1006 in X-ray and Optical Light

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO (Chandra); NASA/MSFC/Nanjing Univ./P. Zhou et al. (IXPE); IR: NASA/JPL/CalTech/Spitzer; Image Processing: NASA/CXC/SAO/J.Schmidt

When the object now called SN 1006 first appeared on May 1, 1006 A.D., it was far brighter than Venus and visible during the daytime for weeks. Astronomers in China, Japan, Europe, and the Arab world all documented this spectacular sight, which was later understood to have been a supernova. With the advent of the Space Age in the 1960s, scientists were able to launch instruments and detectors above Earth's atmosphere to observe the Universe in wavelengths that are blocked from the ground, including X-rays. The remains of SN 1006 was one of the faintest X-ray sources detected by the first generation of X-ray satellites.

This new image shows SN 1006 from two of NASA’s current X-ray telescopes, the Chandra X-ray Observatory and Imaging X-ray Polarimetry Explorer (IXPE). In the full image of SN 1006, red, green, and blue show low-, medium-, and high-energy detected by Chandra. The IXPE data, which measure the polarization of the X-ray light, have been added in the upper left corner of the remnant in purple. The lines in that corner represent the direction of the magnetic field.

NASA's Chandra Rewinds Story of Great Eruption of the 1840s

Your browser does not support the video tag.

Credit: X-ray: NASA/SAO/GSFC/M. Corcoran et al.;

Image Processing: L. Frattare, J. Major, N. Wolk (SAO/CXC)

A new movie made from over two decades of data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory shows a famous star system changing with time, as described in our latest press release. Eta Carinae contains two massive stars (one is about 90 times the mass of the Sun and the other is believed to be about 30 times the Sun’s mass).

In the middle of the 19th century, skywatchers observed as Eta Carinae experienced a huge explosion that was dubbed the “Great Eruption.” During this event, Eta Carinae ejected between 10 and 45 times the mass of the Sun. This material became a dense pair of spherical clouds of gas, now called the Homunculus nebula, on opposite sides of the two stars. The Homunculus is clearly seen in a composite image of the Chandra data with optical light from the Hubble Space Telescope (blue, purple, and white).

A new time-lapse sequence contains frames of Eta Carinae taken with Chandra from 1999, 2003, 2009, 2014, and 2020. Astronomers used the Chandra observations along with data from ESA’s XMM-Newton to watch as the stellar eruption from about 180 years ago continues to expand into space at speeds up to 4.5 million miles per hour. The two massive stars produce the blue, relatively high energy X-ray source in the center of the ring. They are too close to each other to be seen individually.

A Fab Five: New Images With NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory

A new collection of stunning images highlights data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and other telescopes.

Credit: NASA/CXC/SAO, JPL-Caltech, MSFC, STScI, ESA/CSA, SDSS, ESO

A new collection of stunning images highlights data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and other telescopes. These objects have been observed in light invisible to human eyes — including X-rays, infrared, and radio — by some of the world’s most powerful telescopes. The data from different types of light has been assigned colors that the human eye can perceive, allowing us to explore these cosmic entities.

The objects in this quintet of images range both in distance and category. Vela and Kepler are the remains of exploded stars within our own Milky Way galaxy, the center of which can be seen in the top panorama. In NGC 1365, we see a double-barred spiral galaxy located about 60 million light-years from Earth. Farther away and on an even larger scale, ESO 137-001 shows what happens when a galaxy hurtles through space and leaves a wake behind it.

Welcoming a New Member of the X-ray Family

Artist's concept of the XRISM (X-ray Imaging and Spectroscopy Mission) spacecraft.

Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center Conceptual Image Lab

On September 6th, a new X-ray telescope was launched into space, joining the Chandra X-ray Observatory, XMM-Newton, and others already exploring the high-energy Universe.

The X-ray Imaging and Spectroscopy Mission (XRISM, pronounced “crism”) is led by the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency, or JAXA, with contributions from NASA and the European Space Agency.

What will scientists use XRISM for? This feature from NASA describes some of what is can do and the embedded video does an excellent job explaining why ‘spectroscopy’ is so important to astronomers and their study of the Universe. https://www.nasa.gov/feature/feature/2023/xrism-spacecraft-will-open-ne…

Chandra Studies a Moderately Massive Star Destroyed by a Giant Black Hole In Another Galaxy

We are happy to welcome Dr. Brenna Mockler as our guest blogger. Brenna is a postdoctoral fellow at Carnegie Observatories in Pasadena. Her research is primarily on high-energy transients, with a focus on learning about the supermassive black holes in the centers of galaxies and the environments they live in. Prior to her current position, she was a UC Chancellor's fellow at UCLA. She earned her PhD in Astronomy & Astrophysics from the University of California at Santa Cruz in 2022, and a bachelor's degree in Physics from Cornell University in 2016.

At the center of most large galaxies lies a supermassive black hole, larger than our solar system and millions to billions of times more massive than our Sun. These giant black holes influence the evolution of the entire galaxy — for example, they are thought to regulate star formation and their mass is strongly correlated with the mass of the galaxy. Supermassive black holes live in ‘galactic nuclei’ — dense, extreme environments, packed with thousands to millions of times the density of stars that we see in our own night sky.

While we can estimate the bulk characteristics of these nuclei, it is challenging to measure the individual components that make them up. Because there are so many stars packed so closely together, it is very difficult to pick out the unique characteristics of each star. Imagine you are out in the suburbs staring at a distant city skyline — you can tell there is a lot of light, but you can’t pick out the details of each individual lamppost and billboard. However, occasionally one of these stars will pass too close to the supermassive black hole at the center, and get ripped apart by the tidal forces from the black hole in a “tidal disruption event” (TDE).

"El Gordo": A Galaxy Cluster That Pushes the Limits

El Gordo

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/Rutgers/J. Hughes et al.; Infrared: NASA/ESA/CSA, J.M. Diego (IFCA),

B.Frye (Univ. of Arizona), P.Kamieneski, T.Carleton & R.Windhorst (ASU);

When astronomers discovered the galaxy cluster ACT-CL J0102-4915 in 2012 with NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and ground-based optical telescopes, they nicknamed it "El Gordo" (Spanish for the "Fat One") because of its gigantic mass. Scientists estimate that El Gordo contains as much as 3 million billion (3,000,000,000,000,000) times the mass of the Sun. Thanks to its heft, El Gordo acts as a natural lens, distorting the light from more distant objects behind it through a process known as gravitational lensing.

A new composite image of El Gordo shows the diffuse, superheated gas in the cluster observed in X-rays from Chandra (blue) that have been combined with a new infrared image from NASA's James Webb Space Telescope (red, green, and blue). Webb's image shows galaxies in El Gordo plus background galaxies located further away from Earth. El Gordo is located about 7.3 billion light-years from Earth and the background galaxies are at a range of different distances including several that are 12.3 billion light-years from Earth. The appearance of some of the background galaxies has been distorted into a variety of unusual and highly elongated shapes because of gravitational lensing by the cluster.

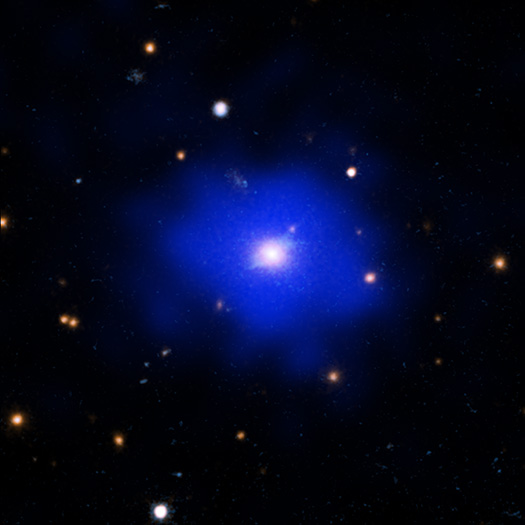

Unexpectedly Calm and Remote Galaxy Cluster Discovered

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/MIT/M. Calzadilla; UV/Optical/Near-IR/IR: NASA/STScI/HST; Image processing: N. Wolk

The discovery of the most distant galaxy cluster with a specific important trait – as described in our press release – is providing insight into how these gigantic structures formed and why the universe looks like it does in the present day.

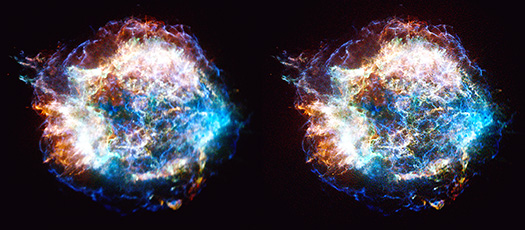

New Technique Improves Clarity of Chandra Images

A team of researchers has announced the development of a new way to process X-ray data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory. This technique will improve the clarity, or sharpness, of some Chandra’s images, including the Cassiopeia A supernova remnant. According to a press release from Rikkyo University in Japan, this new method corrects for the differences in focusing power in different parts of Chandra's images, and could “lead to improved measurement accuracy and the discovery of unknown structures.”

Studies of Past X-ray Flares from Sgr A*

In a new Nature paper astronomers have reported exciting evidence that the supermassive black hole at the center of our Galaxy, Sagittarius A* (Sgr A* for short), produced an intense flare of X-rays about 200 years ago. Sgr A* is 28,000 light-years from Earth, but even from this considerable distance, if a similar flare occurred today then X-ray telescopes like IXPE and Chandra may be damaged if they looked at Sgr A*.

Currently Sgr A* shows frequent but weak outbursts, and has been referred to as a “sleeping giant” by members of the Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration.

In the new study astronomers learned about Sgr A*’s past outbursts by observing X-rays from clouds of gas around the supermassive black hole. While the primary X-rays from previous outbursts would have reached Earth in the past, X-rays reflected from clouds of gas will take a longer path and can arrive in time to be recorded by telescopes like Chandra and IXPE. This idea goes back decades, with the astronomers referring to a paper published in 1980. In the 1990s, several papers reported evidence for X-ray flares from the center of the Galaxy, including one in 1996 titled “ASCA View of Our Galactic Center: Remains of Past Activities in X-Rays?”.

Exploring Stephan's Quintet with Multiple Senses

Stephan's Quintet

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO; IR (Spitzer): NASA/JPL-Caltech; IR (Webb): NASA/ESA/CSA/STScI

Summary

Experts created two new visual and auditory experiences to explore the complexity and beauty of a compact galaxy group known as Stephan’s Quintet. The guided three-dimensional visualization surveys the galaxies — their structures, characteristics, and interactions — captured in multiple wavelengths of light by some of NASA’s great observatories. The sonifications scan two-dimensional images of the quintet, translating the data into sound to reveal the depth and richness this intricate environment holds.

Using data gathered by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, Spitzer Space Telescope, Chandra X-ray Observatory, and James Webb Space Telescope, astronomers and visualization specialists from across several institutions came together to create two new unique sensory experiences of a compact group of galaxies known as Stephan’s Quintet: a video guiding viewers through a three-dimensional visualization of the galaxies, and audio tracks based on two-dimensional observation images. These add to the previously-developed multi-wavelength images, large tactile/audio display table, and small tactile images, bolstering the overall sensory experience of Stephan’s Quintet.