Precocious Supermassive Black Holes Challenge Theories

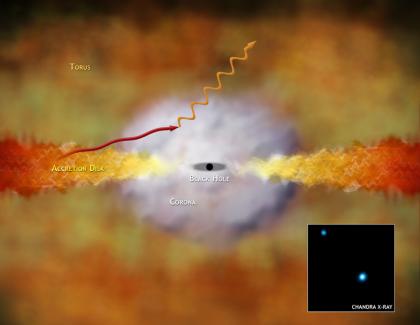

The X-rays observed by Chandra (inset) from the quasar SDSSp J1306 (or J1306) have taken 12.7 billion light years to reach Earth, only a billion years less than the estimated 13.7-billion-year age of the Universe. Surprisingly, in this quasar, which is seen as it was at an early epoch, the distribution of X-rays with energy - the X-ray spectrum - is indistinguishable from that of nearby, older quasars. The smaller object in the upper left of the image is a foreground galaxy.

The X-ray and optical properties of J1306 imply that a billion-solar-mass black hole is the central engine behind its prodigious energy output, which exceeds that of 20 trillion suns. The Chandra results for J1306, and similar XMM-Newton data on another distant quasar, provide evidence that supermassive black holes were fully grown less than a billion years after the Big Bang. This rapid growth is difficult to explain using most current models for the formation of supermassive black holes.

One possibility that might work is that millions of 100-solar-mass black holes formed from the collapse of massive stars in the young galaxy. These black holes subsequently built up a billion-solar-mass black hole in the center of the galaxy through mergers and accretion of gas.

The precise geometry and details of an X-ray producing region around a supermassive black hole are not known. However, it is known that the high-energy X-ray spectra of numerous quasars having a wide range of ages are very similar, so the conditions must be similar.

The accompanying illustration shows how these high-energy X-rays might be produced. Material from a large torus of gas and dust in the center of a galaxy is pulled toward a black hole. Most of the infalling gas is concentrated in a rapidly rotating disk, and a hot atmosphere or corona where temperatures can climb to billions of degrees. Collisions of low-energy optical, ultraviolet and X-ray photons from the disk with the hot electrons in the corona boost the energy of the photons up to the high-energy X-ray range.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The image of the quasar SDSSp J1306 showcases X-rays observed by Chandra (as an inset at bottom left) that have taken 12.7 billion light years to reach Earth. Surprisingly, in this quasar, which is seen as it was at an early epoch, the distribution of X-rays with energy – the X-ray spectrum -- is indistinguishable from that of nearby, older quasars. The Chandra image shows one main bright blue point of light, the quasar. A smaller object in the upper left of the image is a foreground galaxy. In the illustration, at center, there is a black hole, which resembles a dark circle with a bright puffy white ring around it. This ring is reminiscent of a cotton ball. Surrounding the black hole, there is a swirling mass of gas and dust, depicted in shades of orange and yellow. These colors are similar to those found in the sky during a sunrise or sunset. The swirling motion of the gas and dust resembles the movement of clouds in the sky, creating a sense of fluidity and dynamic energy within the space of the image. There are two streaks of light coming from the black hole that are known as a jet, a stream of charged particles that emanates from the black hole and travels millions of light-years into space. The illustration shows the process of how material from a large torus of gas and dust in the center of a galaxy is pulled toward a black hole. Most of the infalling gas is concentrated in a rapidly rotating disk, and a hot atmosphere or corona where temperatures can climb to billions of degrees. Collisions of low-energy optical, ultraviolet and X-ray photons from the disk with the hot electrons in the corona boost the energy of the photons up to the high-energy X-ray range.