Black Holes

Giant X-ray Chimneys and Selection Effects

Astronomers frequently talk about selection effects, where results can be biased because of the way that the objects in a sample are selected. For example, if distant galaxies above a certain X-ray flux – the amount of observed X-rays – are selected for a survey, the most distant objects will tend to be the most luminous, in other words producing the most X-rays.

For doing Chandra publicity we also have a bias, as we are always on the lookout for results where NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory data play a starring role. However, there are many papers where Chandra has an important supporting role instead, and other observatories are the stars. Our colleagues at the European Space Agency (ESA) and the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), have put out press releases on just such a result.

Galactic Center Visualization Delivers Star Power

To look around, either click and drag the video, or click the direction pad in the corner.

(For more information and images, visit: https://chandra.si.edu/photo/2019/gcenter/)

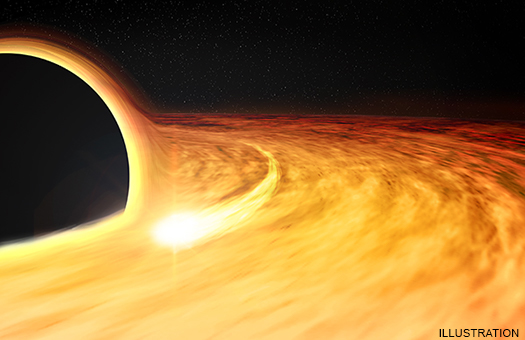

Shredded Star Leads to Important Black Hole Discovery

This artist's illustration shows the region around a supermassive black hole after a star wandered too close and was ripped apart by extreme gravitational forces. Some of the remains of the star are pulled into an X-ray-bright disk where they circle the black hole before passing over the "event horizon," the boundary beyond which nothing, including light, can escape. The elongated spot depicts a bright region in the disk, which causes a regular variation in the X-ray brightness of the source, allowing the spin rate of the black hole to be estimated. The curved region in the upper left shows where light from the other side of the disk has been curved over the top of the black hole.

This event was first detected by a network of optical telescopes called the All-Sky Automated Survey for Supernovae (ASASSN) in November 2014. Astronomers dubbed the new source ASASSN14-li and traced the bright flash of light to a galaxy about 290 million light years from Earth. They also identified it as a "tidal disruption" event, where one cosmic object is shredded by another through gravity.

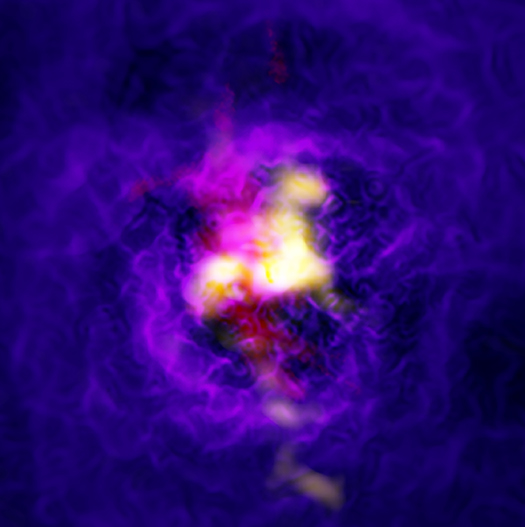

Cosmic Fountain Powered by Giant Black Hole

Abell 2597

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO/G. Tremblay et al; Radio:ALMA: ESO/NAOJ/NRAO/G.Tremblay et al, NRAO/AUI/NSF/B.Saxton; Optical: ESO/VLT

Before electrical power became available, water fountains worked by relying on gravity to channel water from a higher elevation to a lower one. This water could then be redirected to shoot out of the fountain and create a centerpiece for people to admire.

In space, awesome gaseous fountains have been discovered in the centers of galaxy clusters. One such fountain is in the cluster Abell 2597. There, vast amounts of gas fall toward a supermassive black hole, where a combination of gravitational and electromagnetic forces sprays most of the gas away from the black hole in an ongoing cycle lasting tens of millions of years.

Scientists used data from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), the Multi-Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE) on ESO's Very Large Telescope (VLT) and NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory to find the first clear evidence for the simultaneous inward and outward flow of gas being driven by a supermassive black hole.

Cosmic Collision Forges Galactic One Ring — in X-rays

Astronomers have used NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory to discover a ring of black holes or neutron stars in a galaxy 300 million light years from Earth.

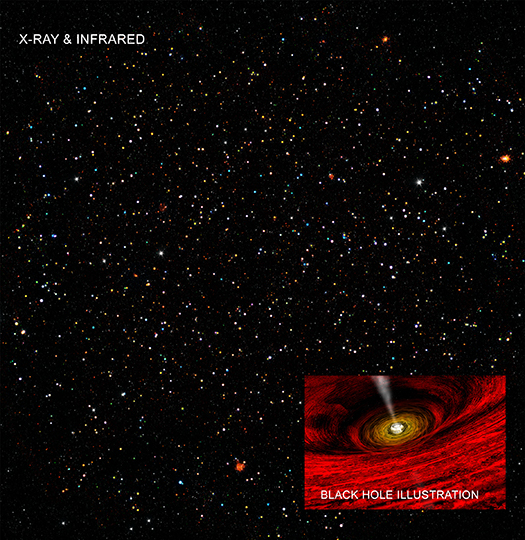

Finding the Happy Medium of Black Holes

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/ICE/M.Mezcua et al.;

Infrared: NASA/JPL-Caltech; Illustration: NASA/CXC/A.Hobart

This image shows data from a massive observing campaign that includes NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory. These Chandra data have provided strong evidence for the existence of so-called intermediate-mass black holes (IMBHs). Combined with a separate study also using Chandra data, these results may allow astronomers to better understand how the very largest black holes in the early Universe formed, as described in our latest press release.

The COSMOS ("cosmic evolution survey") Legacy Survey has assembled data from some of the world's most powerful telescopes spanning the electromagnetic spectrum. This image contains Chandra data from this survey, equivalent to about 4.6 million seconds of observing time. The colors in this image represent different levels of X-ray energy detected by Chandra. Here the lowest-energy X-rays are red, the medium band is green, and the highest-energy X-rays observed by Chandra are blue. Most of the colored dots in this image are black holes. Data from the Spitzer Space Telescope are shown in grey. The inset shows an artist's impression of a growing black hole in the center of a galaxy. A disk of material surrounding the black hole and a jet of outflowing material are also depicted.

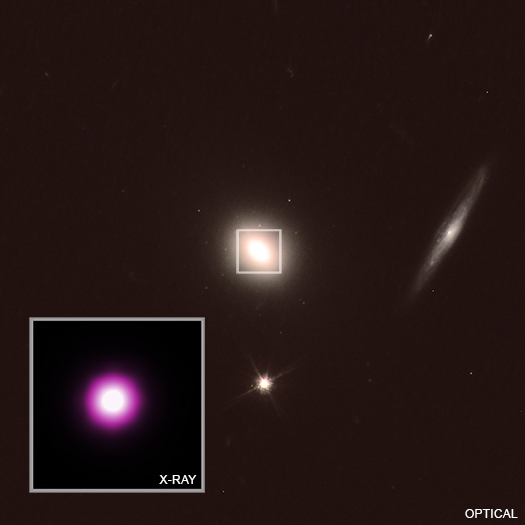

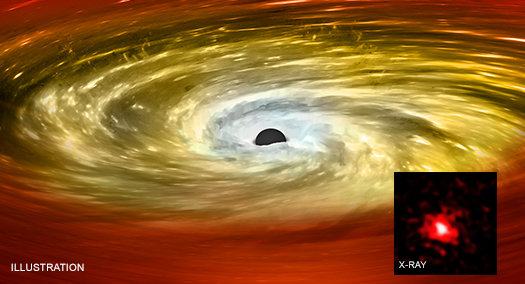

Star Shredded by Rare Breed of Black Hole

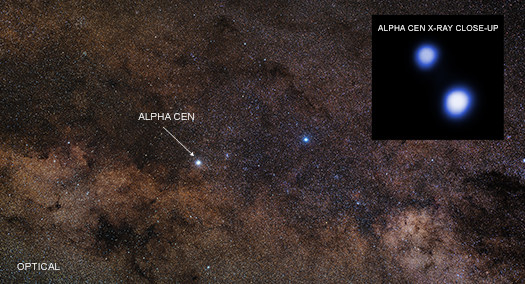

A new study involving long-term monitoring of Alpha Centauri by NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory indicates that any planets orbiting the two brightest stars are likely not being pummeled by large amounts of X-ray radiation from their host stars, as described in our press release. This is important for the viability of life in the nearest star system outside the Solar System. Chandra data from May 2nd, 2017 are seen in the pull-out, which is shown in context of a visible-light image taken from the ground of the Alpha Centauri system and its surroundings.

Alpha Centauri is a triple star system located just over four light years, or about 25 trillion miles, from Earth. While this is a large distance in terrestrial terms, it is three times closer than the next nearest Sun-like star.

The stars in the Alpha Centauri system include a pair called "A" and "B," (AB for short) which orbit relatively close to each other. Alpha Cen A is a near twin of our Sun in almost every way, including age, while Alpha Cen B is somewhat smaller and dimmer but still quite similar to the Sun. The third member, Alpha Cen C (also known as Proxima), is a much smaller red dwarf star that travels around the AB pair in a much larger orbit that takes it more than 10 thousand times farther from the AB pair than the Earth-Sun distance. Proxima currently holds the title of the nearest star to Earth, although AB is a very close second.

Two Neutron Stars + Gravitational Waves = A Black Hole

Dave Pooley

It is a pleasure to welcome Dave Pooley as a guest blogger. Dave led the black hole study that is the subject of our latest press release. He is an associate professor at Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas, where he loves doing research with a cadre of amazing undergraduates on topics ranging from gravitational lensing to supermassive black holes to supernova explosions to exotic X-ray binaries to globular clusters. He lives in Austin with his wife, two (soon to be three) children, two cats, and one dog. When he’s not setting up train tracks, watching Daniel Tiger, or analyzing Chandra data, he enjoys cooking, woodworking, and all manner of whisky.

A colleague of mine at MIT once said that the minute the Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory (LIGO) detects gravitational waves, it will be one of the most successful physics experiments ever performed, and the next minute, it will immediately become one of the most successful astronomical observatories ever operated.

He was exactly right. The direct detection of gravitational waves was a tremendous success for fundamental physics. We knew that gravitational radiation existed, but to directly detect it was huge. It was a triumph due to the meticulous and brilliant work of the hundreds of people who worked for years and years to make LIGO a success.

And immediately with that first detection, astronomers added gravitational waves to our tool belt of ways to study the universe. With just that first event, which was a merger of two black holes, we learned so much more about black holes than we previously knew. That, in turn, raised even more questions about these intriguing objects. Clearly, 60-solar-mass black holes exist. (That was news to us!) And you make them from 30-solar-mass black holes. (That was news to us too!) So 30-solar-mass black holes exist. (Even that was news to us, too!) But how do you make those? We astronomers have a few ideas, but we’re really not sure. We haven’t figured that out yet. Nature of course, already has.

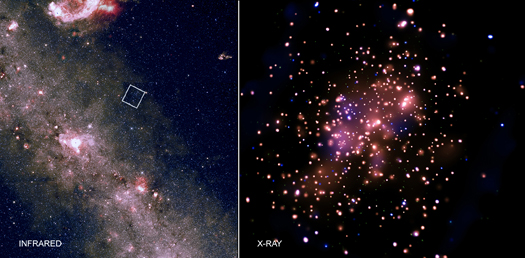

Sagittarius A* Swarm: Black Hole Bounty Captured in the Milky Way Center

In some ways, star clusters are like giant families with thousands of stellar siblings. These stars come from the same origins – a common cloud of gas and dust – and are bound to one another by gravity. Astronomers think that our Sun was born in a star cluster about 4.6 billion years ago that quickly dispersed.