For Release: March 9, 2021

NASA/CXC

X-ray: NASA/CXO/JPL/T. Connor; Optical: Gemini/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA;

Infrared: W.M. Keck Observatory; Illustration: NASA/CXC/M.Weiss

Press Image, Caption, and Videos

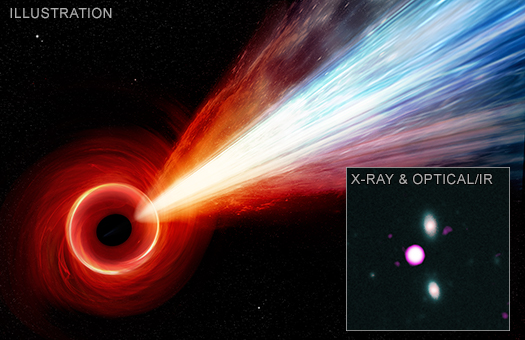

Astronomers have discovered evidence for an extraordinarily long jet of particles from a supermassive black hole in the early Universe, using NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory.

If confirmed, it would be the most distant supermassive black hole with a jet detected in X-rays, coming from a galaxy about 12.7 billion light years from Earth. It may help explain how the biggest black holes formed at a very early time in the Universe's history.

The source of the jet is a quasar — a rapidly growing supermassive black hole — named PSO J352.4034-15.3373 (PJ352-15 for short), which sits at the center of a young galaxy. It is one of the two most powerful quasars detected in radio waves in the first billion years after the Big Bang, and is about a billion times more massive than the Sun.

How are supermassive black holes able to grow so quickly to reach such an enormous mass in this early epoch of the Universe? This is one of the key questions in astronomy today.

Despite their powerful gravity and fearsome reputation, black holes do not inevitably pull in everything that approaches close to them. Material orbiting around a black hole in a disk needs to lose speed and energy before it can fall farther inwards to cross the so-called event horizon, the point of no return. Magnetic fields can cause a braking effect on the disk as they power a jet, which is one key way for material in the disk to lose energy and, therefore, enhance the rate of growth of black holes.

"If a playground merry-go-round is moving too fast, it's hard for a child to move towards the center, so someone or something needs to slow the ride down," said Thomas Connor of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, Calif., who led the study. "Around supermassive black holes, we think jets can take enough energy away so material can fall inward and the black hole can grow."

Astronomers needed to observe PJ352-15 for a total of three days using the sharp vision of Chandra to detect evidence for the X-ray jet. X-ray emission was detected about 160,000 light years away from the quasar along the same direction as much shorter jets seen in radio waves. By comparison, the entire Milky Way spans about 100,000 light years.

PJ352-15 breaks a couple of different astronomical records. First, the longest jet previously observed from the first billion years after the Big Bang was only about 5,000 light years in length, corresponding to the radio observations of PJ352-15. Second, PJ352-15 is about 300 million light years farther away than the most distant X-ray jet recorded before it.

"The length of this jet is significant because it means that the supermassive black hole powering it has been growing for a considerable period of time," said co-author Eduardo Bañados of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA) in Heidelberg, Germany. "This result underscores how X-ray studies of distant quasars provide a critical way to study the growth of the most distant supermassive black holes."

The light detected from this jet was emitted when the Universe was only 0.98 billion years old, less than a tenth of its present age. At this point, the intensity of the cosmic microwave background radiation (CMB) left over from the Big Bang was much greater than it is today.

As the electrons in the jet fly away from the black hole at close to the speed of light, they move through and collide with photons making up the CMB radiation, boosting the energy of the photons up into the X-ray range to be detected by Chandra. In this scenario, the X-rays are significantly boosted in brightness compared to radio waves. This agrees with the observation that the large X-ray jet feature has no associated radio emission.

"Our result shows that X-ray observations can be one of the best ways to study quasars with jets in the early Universe," said co-author Daniel Stern, also of JPL. "Or to put it another way, X-ray observations in the future may be the key to unlocking the secrets of our cosmic past."

A paper describing these results has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal and a preprint is available online. The other co-authors of the paper are Chris Carilli (NRAO, Socorro, New Mexico); Andrew Fabian (University of Cambridge, UK); Emmanuel Momjian (NRAO); Sofía Rojas-Ruiz (MPIA); Roberto Decarli (INAF, Bologna, Italy); Emanuele Paolo Farina (Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics, Garching, Germany); Chiara Mazzucchelli (ESO, Chile); Hannah P. Earnshaw (Caltech, Pasadena, California).

NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center manages the Chandra program. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory's Chandra X-ray Center controls science from Cambridge Massachusetts and flight operations from Burlington, Massachusetts.

Other materials about the findings are available at:

http://chandra.si.edu

For more Chandra images, multimedia and related materials, visit:

http://www.nasa.gov/chandra

Media contacts:

Megan Watzke

Chandra X-ray Center, Cambridge, Mass.

617-496-7998

mwatzke@cfa.harvard.edu

Molly Porter

Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, Alabama

256-544-0034

molly.a.porter@nasa.gov