For Release: April 30, 2015

CXC

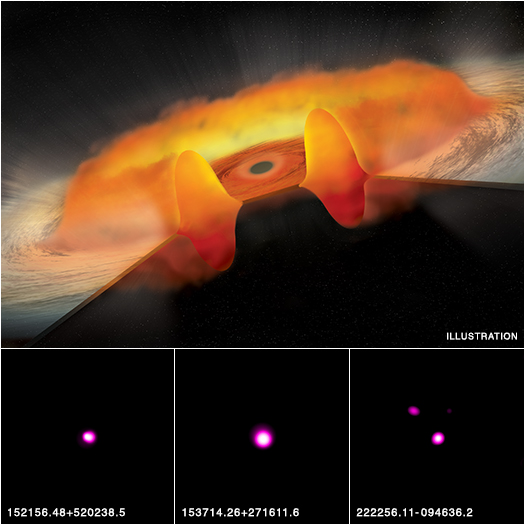

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/Penn State/B.Luo et al.; Illustration: NASA/CXC/M.Weiss)

Press Image and Caption

A group of unusual giant black holes may be consuming excessive amounts of matter, according to a new study using NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory. This finding may help astronomers understand how the largest black holes were able to grow so rapidly in the early Universe.

Astronomers have known for some time that supermassive black holes − with masses ranging from millions to billions of times the mass of the Sun and residing at the centers of galaxies − can gobble up huge quantities of gas and dust that have fallen into their gravitational pull. As the matter falls towards these black holes, it glows with such brilliance that they can be seen billions of light years away. Astronomers call these extremely ravenous black holes "quasars."

This new result suggests that some quasars are even more adept at devouring material than scientists previously knew.

"Even for famously prodigious consumers of material, these huge black holes appear to be dining at enormous rates, at least five to ten times faster than typical quasars," said Bin Luo of Penn State University in State College, Pennsylvania, who led the study.

Luo and his colleagues examined data from Chandra for 51 quasars that are located at a distance between about 5 billion and 11.5 billion light years from Earth. These quasars were selected because they had unusually weak emission from certain atoms, especially carbon, at ultraviolet wavelengths. About 65% of the quasars in this new study were found to be much fainter in X-rays, by about 40 times on average, than typical quasars.

The weak ultraviolet atomic emission and X-ray fluxes from these objects could be an important clue to the question of how a supermassive black hole pulls in matter. Computer simulations show that, at low inflow rates, matter swirls toward the black hole in a thin disk. However, if the rate of inflow is high, the disk can puff up dramatically, because of pressure from the high radiation, into a torus or donut that surrounds the inner part of the disk.

"This picture fits with our data," said co-author Jianfeng Wu of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. "If a quasar is embedded in a thick donut-shaped structure of gas and dust, the donut will absorb much of the radiation produced closer to the black hole and prevent it from striking gas located further out, resulting in weaker ultraviolet atomic emission and X-ray emission."

The usual balance between the inward pull of gravity and the outward pressure of radiation would also be affected.

"More radiation would be emitted in a direction perpendicular to the thick disk, rather than along the disk, allowing material to fall in at higher rates," said co-author Niel Brandt, also of Penn State University.

The important implication is that these "thick-disk" quasars may harbor black holes growing at an extraordinarily rapid rate. The current study and previous ones by different teams suggest that such quasars might have been more common in the early Universe, only about a billion years after the Big Bang. Such rapid growth might also explain the existence of huge black holes at even earlier times.

A paper describing these results appears in an upcoming issue of The Astrophysical Journal and is available online. NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, manages the Chandra program for the agency’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts, controls Chandra's science and flight operations.

NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, manages the Chandra program for NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts, controls Chandra's science and flight operations.

An interactive image, a podcast, and a video about the findings are available at:http://chandra.si.edu

For more Chandra images, multimedia and related materials, visit:

http://www.nasa.gov/chandra

Media contacts:

Megan Watzke

Chandra X-ray Center, Cambridge, Mass.

617-496-7998

mwatzke@cfa.harvard.edu

Visitor Comments (3)

Nothing in the universe is stable. If so, a super massive black holes trillion times the mass of Sun, when explode, will it be similar to big bang explosion? or could it form a parallel universe.

Posted by A.Dharmasiriwardana on Monday, 05.4.15 @ 11:16am

Hi, Many thanks for this posting.

Posted by F Matoofi on Monday, 05.4.15 @ 03:17am

Why no associated jets visible if black holes consuming so much matter? Perhaps objects are too far away to see jets?

Posted by Dr Clive L. Fetter on Sunday, 05.3.15 @ 16:18pm