Most people think of a "telescope" as something in a backyard or the dome at the local planetarium. But telescopes like these that detect the kind of light we can see with our human eyes are just one answer. Stopping there would be like saying, we have cars to get around, who needs airplanes?

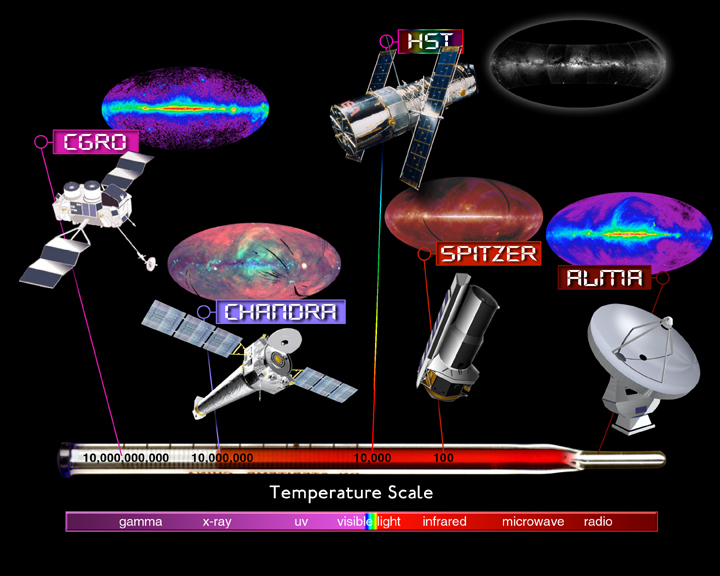

Light takes on many forms - from radio to infrared to X-rays and more. And the Universe tells its story through all of these different types of radiation. So, in order to really understand the cosmos, astronomers need all different kinds of telescopes.

Do we really need these "other" kinds of telescopes? The truth is if we only studied the cosmos in the light we can detect with our eyes, we would only see a small fraction of what was going on. In other words, it would be like trying to figure out the action and score of a baseball game while only seeing down the third base line. By studying all types of light, we can hope to get the full picture of the Universe.

If these other kinds of telescopes are important, why haven't more people heard about them? First, so-called visible light is the best place to start because humans already have a pair of such "telescopes": their eyes. Galileo built on this fact with his telescope in 1609 and work in "optical" astronomy has progressed from there.

Other wavelengths, however, had more difficult starts. For example, X-rays from space are almost entirely absorbed by the Earth's atmosphere. This meant that X-ray astronomy could not begin until humans figured out how to launch satellites and rockets into space in the middle of the 20th century. But X-ray astronomy has grown up quickly and made incredible progress in just a handful of decades.

Think of Moore's Law - the one that says computing power will double every 18 months. X-ray astronomy has been faster than Moore's law, improving 100 million times in sensitivity in just 36 years.

When objects get very hot (or, by extension, very energetic), they give off X-rays. Some of the most intriguing objects in the Universe- black holes, exploded stars, clusters of galaxies-reveal much about themselves through X-rays.

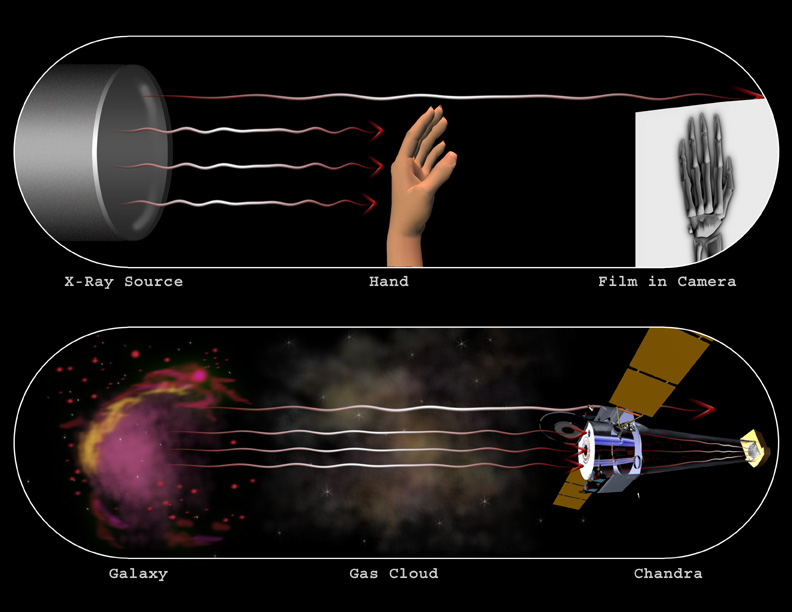

An X-ray machine can't act like Chandra and photograph an X-ray source. Chandra, however, can act like the camera in an X-ray machine and reveal information about what's between the source and the camera.

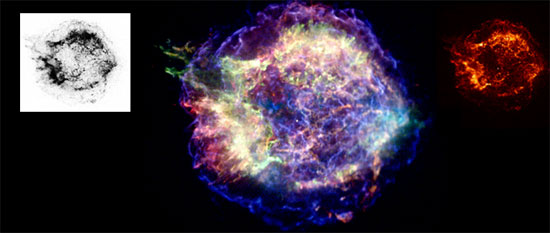

X-rays can't be seen with the human eye, and don't have any "color." Images taken by telescopes that observe at the "invisible" wavelengths are sometimes called false color images. That's because the colors used to make them are not real but are chosen to bring out important details. The color choice is typically used as a type of code in which the colors can be associated with the intensity or brightness of the radiation from different regions of the image, or with the energy of the emission.

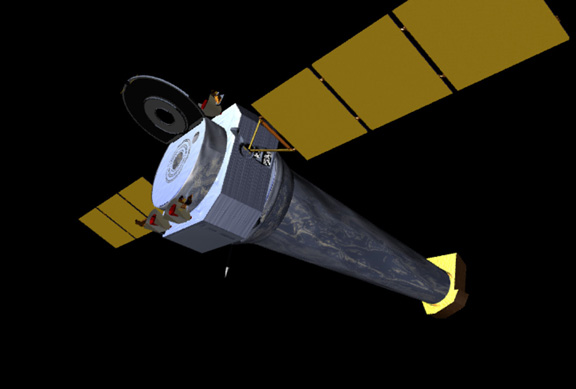

Another reason why a telescope like the Chandra X-ray Observatory is so remarkably successful is that X-ray astronomy is very technically challenging. One of the biggest problems is that X-rays that strike a 'regular' mirror head on will just be absorbed. In order to focus X-rays onto a detector, the mirrors have to be shaped like barrels so that the X-rays strike them at grazing angles, just like pebbles skipping across a pond.

X-ray photons entering the telescope are reflected at grazing angles and focused onto an electronic detector to make an image of a cosmic source.

The Chandra X-ray Observatory captures X-ray images and measures spectra of many high-energy cosmic phenomena. Unlike Hubble, its sister "Great Observatory," Chandra has a highly elliptical orbit that takes it 1/3 of the way to the Moon. This orbit allows Chandra to observe continuously for many hours at a time, but makes it unreachable by the Space Shuttle, which was used to launch it back in 1999.

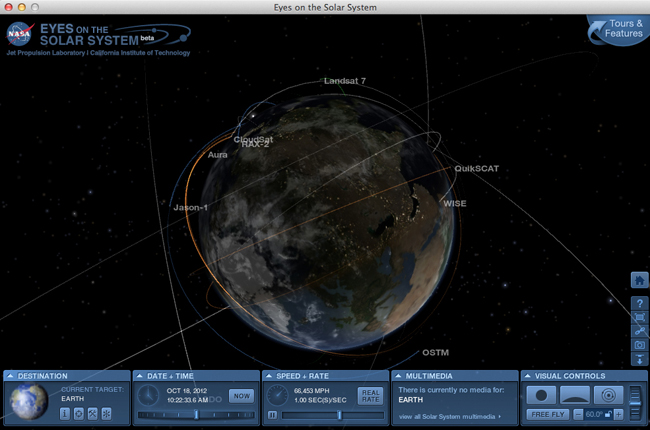

The X-ray data obtained by Chandra is typically stored on board for about 8 hours worth at a time. About three times a day, Chandra communicates with the Deep Space Network, sending its newly acquired data back to Earth while receiving new instructions from the ground.

The Deep Space Network consists of three dishes in Australia, Spain, and California. It is the primary way (think of a cosmic phone line) that Earth maintains contact with missions through the Solar System.

This Google Earth video shows the three locations of the Deep Space Network (Spain, Australia, and the US). Next you'll zip to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in California and then you'll complete the trip at the Chandra Operations Control Center and the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Massachusetts, US.

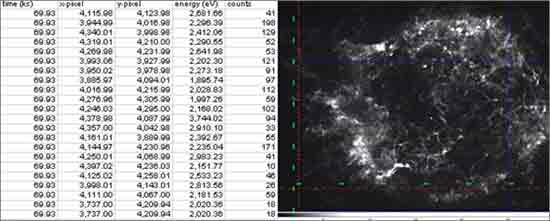

The data transmitted via the Deep Space Network doesn't come in the form of polished images or spectra. Rather, it appears as a series of positions and times. The tables of information can then be translated into an image, for example, by plotting the position on a grid. Each additional photon for a location makes that point appear brighter, thus representing a stronger X-ray source.

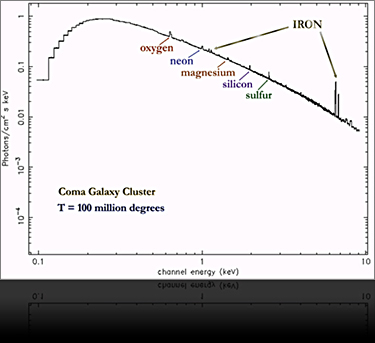

If astronomical images are considered the equivalent of crime scene photos, then spectra are the fingerprints. While difficult for the untrained eye to decipher, spectra reveal a wealth of information about the Universe.

Spectroscopy, the study of which atoms absorb and emit light, can reveal the chemical composition of cosmic objects. Spectra can also reveal information such as temperature and velocity of different features of an object.

For many of us, it is astronomical images that piques our interest and imagination. From the numerical data that is transmitted from the satellite, multi-colored X-ray images can be made. By assigning different parts of the X-ray range that Chandra observes to colors recognizable to the human eye, we are allowed to see the invisible.